A publication of the Association of California School Administrators

What the growing funding gap means for you

What the growing funding gap means for you

Basic aid districts create financial disparities — here's how to plan for them

Basic aid districts create financial disparities — here's how to plan for them

As a school administrator in California, you’re used to navigating a complex and often challenging financial landscape. You’re tasked with maximizing every dollar to provide the best education for your students. But a recent report, “Excess Revenue, Unequal Opportunity: Revisiting Basic Aid in the LCFF Era,” from Bellwether and PACE, highlights a stubborn and growing problem that makes your job even harder: the outsized financial advantage of what are known as “basic aid” districts.

You might call them “community-funded” or even “excess tax” districts, and a recent report refers to a subset of them as “well-resourced” but the name doesn’t change the facts. While California’s funding system, the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), was designed to promote equity, the persistence of these districts creates a significant financial disparity that can affect your ability to raise student achievement, compete for talent, manage enrollment, and plan for the future.

What exactly is a basic aid district?

To put it simply, a basic aid district is a school district whose local property tax revenues, plus a small amount of state aid, are greater than the funding target set by the state’s LCFF formula. The term “basic aid” comes from a constitutional requirement that the state provide a minimum amount of state aid to every district, regardless of its property wealth.

While most districts rely on the state to fill the gap between their local property taxes and their LCFF funding target, basic aid districts are so property-wealthy they don’t need that state funding. In fact, they get to keep the property tax revenue that is “in excess” of their LCFF entitlement. This gives them a powerful advantage that isn’t available to other districts.

The numbers tell a sobering story

Don’t be fooled by their small number. While basic aid districts make up only about 15 percent of all districts and serve just over 5 percent of California’s students, the money they receive is substantial.

Growing revenue: The total amount of excess local revenue collected by these districts has increased by 41 percent over the past five years.

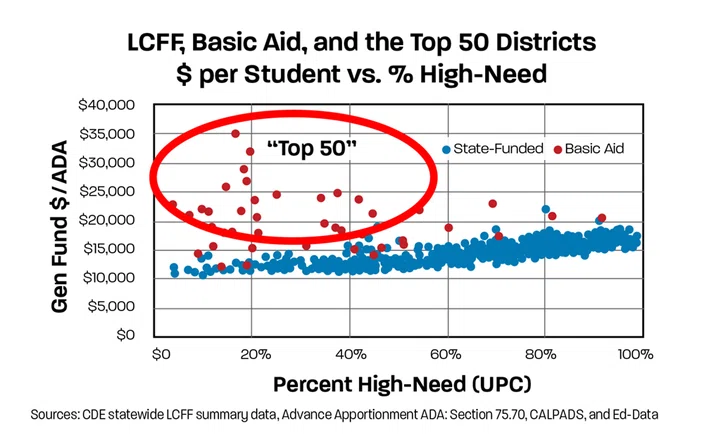

The “Top 50”: The report identifies a subset of 50 “over-funded” basic aid districts. These districts have both a high amount of excess revenue (over $5,000 per pupil) and a low percentage of high-need students (55 percent or less).

Massive disparity: These 50 districts alone generate about $1.15 billion in excess revenue annually. That’s 87 percent of the total excess revenue generated by all basic aid districts.

Growing gaps: The funding gap between neighboring Top 50 and LCFF districts has grown dramatically, in many cases doubling or even tripling in the last 10 years. Gaps in excess of $10,000 per student are common.

Why this matters to you: The operational impact

This isn’t just a high-level policy issue; it has direct operational implications for your district, especially if you’re not in a basic aid district.

Teacher talent and salaries: The biggest impact is on the labor market. The report found that the “Top 50” basic aid districts offer average teacher salaries that are

$27,000 higher than LCFF-funded districts. They also have a higher percentage of fully credentialed teachers and smaller class sizes.

Think about San Jose Unified School District in Santa Clara County. SJUSD leaders report that they lose educators and administrators to neighboring districts that can offer substantially higher salaries. In Santa Clara County, where SJUSD is located, “Top 50” districts pay an average of $35,000 more than LCFF-districts, with smaller class sizes and a higher share of fully credentialed teachers.

Recruiting and retaining staff: This financial advantage allows these districts to out-compete their neighbors when it comes to attracting qualified educators. If you’re in a non-basic aid district, you’re competing on an uneven playing field, making it tough to recruit and retain the staff you need, especially if you’re located near one of these “well-resourced” districts.

Enrollment and financial planning: If you’re an LCFF-funded district with declining enrollment, you’re losing money with every student who leaves. Basic aid districts, on the other hand, don’t rely on state aid tied to enrollment, so they’re less concerned with student fluctuations and less likely to accept interdistrict transfer students, as these students don’t bring in additional dollars. This makes it even harder for districts with declining enrollment to stabilize their finances.

What are the solutions?

The report outlines five possible policy options to address these disparities. While some are more politically feasible than others, they all aim to make the system more equitable.

Capture and redistribute excess taxes: This is the most direct solution. The state could capture some or all of the $1.3 billion in excess revenue from basic aid districts and redistribute it to other districts. This could be done statewide, but a county-based approach might be more politically palatable and could avoid some constitutional hurdles.

Provide more state aid to lower-wealth districts: Rather than “leveling down,” the state could “level up.” This would involve increasing state funding for districts with less local property wealth. The challenge, of course, is finding the money for this.

Encourage district consolidation: The state could incentivize smaller districts to consolidate or share services. This would pool resources and spread the tax base across a larger number of students, promoting greater equity and efficiency.

Expand interdistrict transfer: The state could make it easier for students from LCFF districts to transfer to basic aid districts. This would give students access to the richer resources of basic aid districts without redrawing district lines. However, this could be met with resistance from both LCFF and basic aid districts.

Implement regional cost adjustments: The LCFF could be modified to include regional cost adjustments, providing more funding to districts in high-cost areas that struggle to pay competitive salaries. This would help many LCFF-funded districts without affecting the funding of the highest-revenue basic aid districts.

Conclusion

Jerry Brown, the governor of California who grandfathered LCFF, said: “My 2013 Budget Summary lays out the case for cutting categorical programs and putting maximum authority and discretion back at the local level — with school boards. I am asking you to approve a brand new Local Control Funding Formula which would distribute supplemental funds — over an extended period of time — to school districts based on the real world problems they face. This formula recognizes the fact that a child in a family making $20,000 a year or speaking a language different from English or living in a foster home requires more help. Equal treatment for children in unequal situations is not justice.”

California’s education funding system was built on the principle of equity, but the reality of basic aid districts challenges this core vision. The growing gap in resources between basic aid districts and their peers is a major issue that needs to be addressed through broader reform. As education administrators, understanding this dynamic is crucial for strategic planning, advocacy, and ensuring that all students in your community have the resources they need to succeed.

Lisa Andrew, Ed.D, is CEO of the Silicon Valley Education Foundation and former superintendent of Hollister School District. Todd Collins is a former board member with Palo Alto Unified School District.

ADVERTISEMENT