A publication of the Association of California School Administrators

Unveiling the magic potion for an engaged classroom

Behavior management boils down to two things: An asset-based approach and the ABCs of behavior

Imagine the following scene: A toddler pushes a chair, climbs up on it until he is standing and he sees his goal: a glass jar of cookies on the counter. How do we respond? As a parent, you might be amazed at this first-time prowess and are ready to intervene just at the appropriate time. Perhaps you even give him a cookie when he reaches his goal. Amazing, isn’t it? Now let’s look at this scene again: the pushing of the chair, the climbing on it, but this time it is to reach a boiling pot on the stove. How do we respond?

To the toddler, both situations are the same, but your response is different. Why? Why is it inconsistent? That is hard to understand. You can explain it simply. The consequences of the first behavior were not dangerous like the second one. Confused yet? So are our students and the adults who care for them.

Over the last 25 years as educators, we have heard many stories about behavior that has prompted adults to act in ways that were confusing for students and for themselves. We hear emotional outbursts like, “How could she or he do this to me?” “I think the teacher hates me. She punishes me for everything. Suzy did the same thing and it’s OK.” The adults say, “That is a trigger for me. It’s too much!” As students get older, you see more severe and intense eruptions that can be scary for all of those involved, even dangerous. Students confronting teachers, teachers confronting students, groups taking sides, voices are raised and actions are taken that can be immediately regretted, or if not, they should be.

So, what can we do? How can we see student behavior as just a reaction? How can we learn to respond in a way that is beneficial for all, without additional costs? In this article, we will introduce a free and highly effective classroom strategy that will result in a successful learning environment if you are ready to maintain your cool and do the best for that student, in that situation, and in that context.

Before we teach any subject area, we assess our students informally or formally, gathering data on their current levels of proficiency. This baseline data is then used as a way to help students move from their zone of proximal development to independence. So before introducing one of the many behavior-based programs to teach our students how to interact with each other and adults, why not start by getting to know them first and trying a simple strategy? In our own experiences as students, there are times we have been treated like we were blank canvases that needed to be taught or trained on a new concept without any regard to what we bring to the classroom. But if our teacher had taken the time to know our strengths, our learning would have felt empowering, synergistic and uplifting. Through years of trial and error, going through a myriad of programs for classroom management and systemic changes, we are proud to unveil a magic potion that may reframe how you visualize and experience teaching. So, let’s get started.

The magic potion

Our strategy, the magic potion, is an amalgamation of two research-based approaches (or ingredients) to teaching and learning:

1. Asset-based approach 2. ABCs of behavior

In any instructional environment, you want to start by getting to know your learners. Thus, the first ingredient in this magic potion is an educational pedagogy that has the capacity to empower human development. It is an assets-based approach to teaching. The California Department of Education has articulated a commitment to educational equity for all students in California with asset-based pedagogies that view the diversity that students bring to the classroom, including culture, language, disability, socio-economic status, immigration status and sexuality as characteristics that add value and strength to classrooms and communities. Gloria Ladson-Billings’ (1995) introduction of culturally relevant pedagogy describes a form of teaching that calls for engaging learners whose experiences and cultures are traditionally excluded from mainstream settings. All learners process new information best when it is linked to what they already know.

In a classroom where the teacher uses culturally relevant pedagogy, learners’ varied identities and experiences are identified, honored and used to bridge rigorous new learning. In an increasingly diverse society, all students benefit from learning to honor their own and one another’s cultural heritage and lived realities. And asset-based pedagogy similarly focuses on identifying and building upon student strengths using the funds of knowledge approach. What assets does the student bring to the table? What skill do they need to work on? What do they know already? Where do we start? Teachers examine their students’ diverse backgrounds through various lenses such as economics, geography, politics, technology, religion, language, art, etc. (Kelly, 2020).

Let’s shift our focus now to the second ingredient, the ABCs of behavior, which is a model of behavior modification used in educational and therapeutic settings. It is how you make sense of what is happening in your environment to identify the function of certain behaviors. How do these two ingredients that are from different fields such as behaviorism and education, yet grounded in research, amount to magic? When used in tandem, we holistically anchor students’ assets to facilitate desired behaviors ultimately promoting a positive and safe learning environment.

Turning magic into practical solutions

Taking into consideration these two integrated approaches to teaching that can be applied to behavior, teachers can proactively analyze the classroom capital first. Teachers typically relate to these considerations when it comes to academics, but let’s be real — when a student does not know how to add, it doesn’t necessarily affect the whole classroom, only that child, right? Schools are getting better at developing and organizing academic interventions and with behavior, we need to do the same thing.

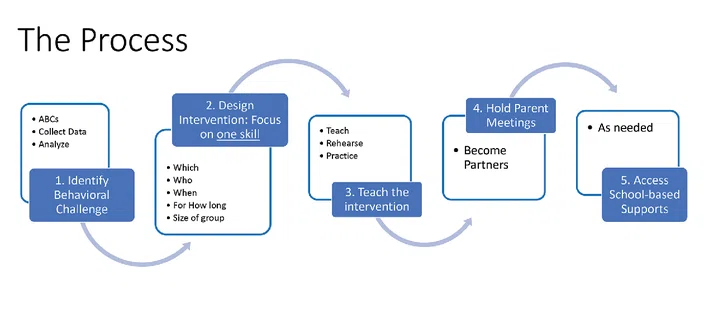

Always based on data, there are five proactive steps to build an engaged classroom:

1. Identify the behavioral challenge using ABCs

Just like in the case of the asset-based approach where in the past a deficit pedagogy model was used, traditional approaches to discipline have been punitive in nature, where the emphasis has been to punish or suppress behavior.

Teachers can start by collecting data to help set up their classrooms. They can document the type of unwanted behavior, the frequency of the behavior, time of day, etc. This will serve as the basis for designing any interventions. If the behavior continues, teachers need to identify the ABCs of the behavior (Meadan et. al., 2016), which can serve as a diagnostic tool to understand the function of the behavior. Sometimes in our fast-paced teaching environment, when we see an unwanted behavior being repeated and it does not make sense to us, we just ignore it or let it go, unless it causes major disruption in the classroom. However, a problem arises when the behavior is negatively affecting the child, his/her peers and the adults. Then we have to figure out what is going on using the ABCs of behavior. What are antecedents? These are the triggers, the cues, prompts, signals, questions, commands and reactions. What is the undesired observable behavior? Behavior is observable, measurable, and the action or reaction of the individual to the environment or antecedent, and can be clearly defined. What are the consequences of the behavior? Let’s be very clear — consequences are not punishments. They are the natural consequences of a behavior. They are the outcome or feedback that occurs immediately following the behavior. Positive corrective feedback helps students learn and use appropriate behavior in the future.

For example, if you touch something extremely hot, the consequence is that you will get burned. But maybe you were trying to reach a spoon and that was your focus. Before we can identify the function of the students’ behavior, or why they are doing it, we need to look at this as a science and collect data. What happened before the behavior, what exact behavior are we trying to address and what are the consequences. Once we can understand that, we move toward identifying what the function of the specific behavior is: To avoid or to gain something in particular.

As a word of caution, remember that sometimes our frustration with disruptive behavior causes us to make blanket statements: He/she just does not know how to behave. They need to go to another class. Their being here is just too disruptive to everyone else’s learning. This rejection can actually exacerbate the unwanted behaviors due to the fact that the student would rather avoid your class or your presence. It is harsh to say this, but it goes both ways. Unbeknownst to them, the teacher might actually be the trigger for the unwanted behavior. So, keeping this in mind, take the time to calmly review the data. What does it tell us?

First, let’s identify the most pressing need or an observable behavior that could be corrected right away by focusing on one single observable behavior using an observation tool (Dubie and Pratt, 2022).

A. Remember the antecedents? What happened right before the behavior happened? What was the setting? Any players? Any actions or directions? Were there any possible triggers?

B. Describe the observed behavior.

C. What are the consequences? What happened as a consequence of the behavior? What happened right after the observed behavior? What did the student do? What did you (the teacher) do? What did the other students do?

Again, this data has to be reviewed carefully and as objectively as possible. If you need to, you might consult with other educators or experts on behavior as well as parents to shed some light on the matter. While setting up a reading intervention, we perform a running record on a student’s reading of a passage and then we analyze it to design a mini lesson for the reading skills that need reinforcement. Similarly, with behavior intervention we suggest that you start by designing a small intervention.

2. Design an intervention

Teachers need to explicitly teach and reteach behavior expectations contextually, bringing in the collective classroom capital, and practice them routinely. They cannot expect students to “know” the desired behaviors. Some students might and others may not. If teachers notice a pattern with a student who is having a difficult time following expectations, they can intervene immediately and reteach the expectation. The best way to reteach it is to do it without singling out the student, which could be through reteaching the whole class as regular practice and referencing or positively reinforcing good examples. As soon as you see your student doing it correctly, you can also use this behavior as an example for the class.

Now that we understand the behavior and have analyzed it, we can think of how we will approach this. Select one skill the student needs to work on. Which skill will be addressed? Try to select a skill that will be easier to learn and will take them quickly to the desired behavior. That way, your student will feel successful sooner rather than later. Maybe the intervention will just involve changing the environment, an environmental strategy. It all depends on your analysis. Maybe every time your student enters the classroom, he hits something on the bulletin board. An intervention for this behavior could be simply to remove that item. You need to brainstorm several strategies that address exactly the one skill you found in your analysis that you want to target. Since this intervention is classroom based and for all your students, it is considered a Tier 1 foundational intervention. School-based supports for some students or individualized prevention are referred to as Tier 2 or 3 respectively (Center on PBIS, n.d.).

To design the Tier 1 intervention, think about these things:

- Time of day the intervention will take place.

- Who will provide the intervention? (Start with the teacher for Tier 1.)

- Duration. (How long/often will we teach the new skill?)

- Intensity (size of group) when we teach, rehearse and practice.

Teachers can start by collecting data to help set up their classrooms. They can document the type of unwanted behavior, the frequency of the behavior, time of day, etc. This will serve as the basis for designing any interventions.

3. Teach the intervention by choosing one teaching strategy

What instructional strategy will you use to help the child learn the new skill you identified? The selected strategy needs to be evidence-based, which means it can be measured and you can collect evidence as you implement it.

Once you decide how to teach the new behavioral skill, you need to think about when and in what context the skill will be taught, and for how long. Try something you think you can do quickly. As mentioned before, an environmental strategy might be all you need. Maybe rearranging the desk or group formation will be sufficient. Keep track of the results of this change. You still have to teach your students the new routine, rehearse it and let them practice it.

- Teach by connecting to your students’ collective funds of knowledge.

- Rehearse.

- Practice independently.

ADVERTISEMENT